WRAL Doc: New Trouble on the Neuse River

In 1990, the Neuse River was on the brink of catastrophe. Thirty years later, the Neuse is in trouble again. Four prominent scientists who helped WRAL to study the Neuse back then agreed to help again. We also interviewed local and state political leaders, river keepers, activists and fishermen about the state of the Neuse and what must be done to protect it.

Posted — UpdatedBringing the Neuse River back from the brink

In 1990, the Neuse River was on the brink of catastrophe. Nutrient pollution was robbing this river of so much oxygen that fish were dying by the millions every day. Toxic algal blooms threatened the river as a source for drinking water. People complained of strange burning sensations after swimming in the river.

To investigate the problem, WRAL researchers and reporters sought out experts from North Carolina universities and the Environmental Defense Fund to analyze wastewater along the Neuse from Hillsborough in Orange County to Ocracoke at the end of Pamlico Sound. The documentary that followed was screened at the state legislature, and lawmakers took action – across the aisle – to develop a bi-partisan plan to combat river pollution.

But something went wrong. The carefully crafted plan to save the Neuse River was blown off track.

Thirty years later, the Neuse is again in trouble.

“In a nutshell, the river is in very poor health and declining and continuing to decline,” says Dr. JoAnn Burkholder, aquatics ecologist at North Carolina State University.

Four prominent scientists who helped WRAL to study the Neuse in the 1990s agreed to help again. We also interviewed local and state political leaders, river keepers, activists and fishermen.

Get to know the Neuse

Native Americans called the Neuse “River of Peace.” It is a fitting name for the gently flowing waterway. Compare it to the mighty Cape Fear to the south and the raging Roanoke to the north.

The Neuse rises in the Triangle near Hillsborough and flows 275 miles past Raleigh, Smithfield, Goldsboro and New Bern before it empties into Pamlico Sound.

“This is an incredible water resource that North Carolina has, a world-class-resource system, “ says Stan Riggs, a marine geologist at East Carolina University.

Burkholder adds, “It is considered the number one most important nursery ground for fish from Maine to Florida. They come to that estuary to spawn. The young grow and then they move north or south.

"It is the second largest estuary on the U.S. mainland and the most important fish nursery ground.”

The late James Barrie Gaskill made his living fishing those waters. He revered the Neuse and passed on his respect to son Morty, a commercial fisherman now at age 25.

“Water is a public trust resource, and it belongs to everyone, and you’ve really you’ve got to maintain its health for the health of society," Morty Gaskill says.

But not everyone feels so strongly about protecting these waters.

Another Native American name for the Neuse was “guatano,” which means “pine trees along the water.” Today many of the trees along the river are gone – cut down by industry, farmers and developers.

“You clear-cut, you clear-cut and you build and then you build. Add a little trivial planting around there and you think you’ve done a good job. That’s baloney," Riggs says.

The lack of buffer zones along the Neuse emerged as a major pollution issue in 1990.

The General Assembly responded by establishing a 50-foot vegetative buffer along the Neuse. Some lawmakers favored a 100-foot buffer like the one along the Chesapeake Bay. Both Democrats and Republicans in the North Carolina Legislature took other actions to protect the Neuse following our reporting in the 1990s.

“In the early 1990s and late 1980s was when the confined animal feed industry, especially swine, moved in and so the whole watershed was really shifting," Burkholder says.

The legislature ordered a moratorium on new industrialized hog farms because of the enormous amounts of nutrient waste they generate. Crop farmers, meanwhile, agreed to dramatically reduce their fertilizer use.

Rick Dove, the original Neuese riverkeeper and a former U.S. Marine attorney had nothing but praise for those efforts.

“The crop farmers, traditional family farmers, have done a magnificent job," he says.

Burkholder concurs. “Big kudos to them," she says. "They reduced their nitrogen applications by 40%. That’s big!”

Cooperative action sets Neuse on course to recovery

Cities along the river joined the battle to save the Neuse as well. Municipal wastewater treatment plants on the river sharply cut nutrient discharges over the next decade. Kinston Mayor Don Hardy says, "If everybody plays their part, then we will be at a better place.”

It was an impressive effort.

Hurricane Floyd's floods inundate the Neuse with waste

Progress to heal the Neuse River from paralyzing pollution was slow as the 21st century approached. Scientists say it’s never a quick fix when you’re dealing with nutrient pollution.

Hans Paerl, environmental scientist at the University of North Carolina Institute of Marine Sciences, says it's always a matter of effort plus time.

"The remedy is: reduce the input and let the system cleanse itself, and that can take decades. This is the truth about natural systems,” he says.

Hurricane Floyd in 1999 was an environmental disaster, spewing pollution all over the Neuse River and into Pamlico Sound.

Flooding caused hog waste lagoons on industrialized farms to overflow and mix with floodwaters. The state responded by buying out some of the farms in flood plains, but many remain today.

"The Neuse still has close to 2 million hogs that are being grown with outmoded, last-century technology in waste treatment," Rader says.

Hog farm companies defend their technology, saying it’s worked for years in Midwest.

But there’s a big difference. There’s a thick layer of soil – at least 20 feet – over the water table in the Midwest compared to only three feet in eastern North Carolina.

“So, there is an incredibly thin layer of soil that cannot possibly absorb that waste," Burkholder says.

Plus, the Midwest doesn’t have the world-class water system of eastern North Carolina with our major rivers and coastal estuaries.

Legislative leadership change rolls back regulations that protect rivers

Lower Neuse Riverkeeper Katy Langley rides the river every week looking for signs of pollution.

"I collect the evidence and I photograph it," she says. “I make sure it has a GPS point on it, and I send it to the North Carolina Department of Environmental Quality so they can open up a formal investigation.”

River advocate Rick Dove checks for polluters by air.

“We have so much waste that is being produced by swine and poultry that it’s almost impossible to comprehend," he says.

Dove and Langley also look for signs of pollution from other industry, wastewater treatment plants and developers who build close to the water.

They’ve been very busy since Hurricane Florence in 2018.

Given the time it takes for the river basin to recover environmentally from a major hurricane, too many big storms close together could devastate fisheries and water quality

“The thing we are really worried about is with this new increased frequency in hurricanes," says Paerl, the UNC environmental scientist.

When Republicans took control of the Legislature in 2012, they vowed to cut regulations to help grow the economy.

“We have reduced some of our rules and regulations which has made it easier for businesses to expand,” says Sen. Brent Jackson, a Sampson County Republican.

Scientists strongly disapproved when the lawmakers eliminated buffer rules. The General Assembly also slashed the budget for the Clean Water Trust Fund by 90% and made what many called “draconian” cuts to the state environmental budget.

“So right now the state does not have the ability to get out there and even know if anyone is polluting in the waters," says Rep. Grier Martin:, a Democrat whose district includes north Raleigh.

Langley sees that in her patrols of the Neuse.

"Everything keeps falling through the cracks constantly. They can't keep up with it because they don't have the resources or the staff," she says.

Upper Neuse Riverkeeper Starr sees an even more pointed political connection. “Our political climate in Raleigh on Jones Street does not favor the health of this river or our environment in general,” he says.

NC State's Burkholder agrees with that assessment. She points to a 2015 study ranking North Carolina next to last in environmental spending nationwide at $8 per capita with only Oklahoma spending less.

And it’s not that fish kills have gone away. They still happen. They don’t get as much attention now that the state has eliminated its Fish Kill Rapid Response Team.

Grading the Neuse River

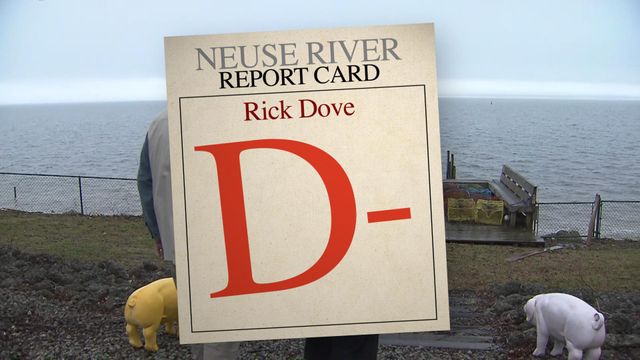

WRAL returned to four prominent scientists who have studied the Neuse River for decades to ask each to give a letter grade for this waterway. They agreed that North Carolina can and must do more to protect water quality.

"The message from Florence is really simple: Wake up," says Rader, of the Environmental Defense Fund.

"A huge amount of effort was put into building plans and building programs and funding them to help bring the Neuse from the brink of catastrophe in the 1980s and 90s," he says, but that level of effort has waned even as North Carolina grows.

He gives the Neuse River a grade today of C-minus

Scientists are fearful of another issue: a new EPA proposal to roll back protection of wetlands, ponds and streams.

Burkholder says that in 25 years of water quality data, she has seen no decrease in total nitrogen. Nitrogen and phosphorus from urban runoff, farms and industrial discharges rob the river of oxygen, killing the fish and putting drinking water at risk.

She reluctantly gives the Neuse River today a grade of D-minus. “I think it’s an unfair question," she says. "It’s not the river’s fault!”

Paerl’s research has shown some signs of improvement. He gives the Neuse a C, but says we have got to get a handle on toxic algal blooms.

“Those toxins, if taken in, in drinking water, can lead to liver issues, digestive issue and even neurological symptoms," he says.

Riggs, a marine geologist at ECU, gives the Neuse of grade of D-plus with a stern recommendation that North Carolina dramatically upgrade environmental education.

“Jeepers! Clean water is really important," he says. "Abundant water is really important. Why? Because there isn’t going to be anymore if we’re not careful.”

River advocate Rick Dove, who has been fighting pollution for 50 years on the Neuse, believes some hard choices are in the offing.

“We are trying to hold on to the resource without offending the polluters. I don’t know how long the Neuse is going to put up with that," he says.

Martin, the Raleigh representative to the state house, sees it as a economic driver. “There is no way we’re going to bring jobs to North Carolina if the people that move here can’t be assured of both quantity and quality of drinking water,” he says.

Kinston Mayor Don Hardy sees another opportunity for cooperation and collaboration.

“You put aside politics," he says. "You’ve got to have that bipartisan approach to make things happen for the people as a whole. You don’t play politics when you’re talking about people’s lives.”

Morty Gaskill says cleaner water is essential for survival of commercial fishing.

“All of those little fishing villages in this section of the state, they don’t exist anymore," Riggs adds.

“North Carolina needs to reawaken our environmental ethic,” Rader says. “Reawakening the spirit of ‘yes.’ Yes for nature and man together. People together. Communities together. This is essential for the future!”

North Carolinians can start by making sure we and our families are not contributing to the pollution problems of the Neuse River with unnecessary and careless use of fertilizers and chemicals on our lawns. We can teach our children and grandchildren to become environmental watchdogs or volunteers to take water samples. And we can demand from our state lawmakers a new bi-partisan comprehensive plan to protect this river for future generations.

Related Topics

• Credits

Copyright 2024 by Capitol Broadcasting Company. All rights reserved. This material may not be published, broadcast, rewritten or redistributed.